International ADR

summary

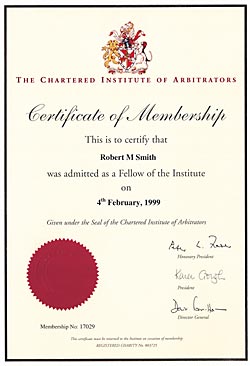

Mr. Smith is a Barrister of the Inner Temple in England, and was an Associate Tenant at Littleton Chambers in London. He is also a Chartered Arbitrator in England, and a member of the Mediation Panel in London of the Chartered Institute of Arbitrators. He has been a Médiateur Agréé with the Centre de Médiation et d’Arbitrage de Paris (CMAP).

He supervised foreign litigation worldwide for the Bank of America. He has appeared in the International Court of Justice at The Hague. He is a member of the London Court of International Arbitration, and the Arbitration Committee of the International Chamber of Commerce (Paris).

He has taught at Oxford University and the UN’s International Labor Organization in Turin, Italy.

He has mediated in several countries.

He is, or has been, on the panels of centers in Cairo, Hong Kong, Kuala Lumpur, Singapore, and Vancouver, and an Associate Member of the Australian Centre for International Commercial Arbitration.

Mr. Smith is an Elected Fellow of the International Academy of Mediators.

Mr. Smith has been published in The Bulletin of the Commercial Arbitration Centre for the Gulf Cooperation Council (Bahrain) and in the Newsletter of the Regional Centre for Arbitration Kuala Lumpur. The articles covered such topics as combining arbitration and mediation, drafting arbitration clauses, mediating international intellectual property disputes, and international mediation generally.

Here, a distinguished colleague, Jan Paulsson, provides a practical guide to international arbitration, which can be a sensitive process — with some attention to mediation and conciliation.

Four immediate thoughts may strike a lawyer contemplating for the first time the prospect of international arbitration. First, one or more of the arbitrators may be foreign. Second, the arbitration may, in whole or in part, be conducted abroad. Third, evidence may be produced, or sought to be produced, from foreign sources. Fourth, the logical place to enforce the award may be abroad.

Further, each of these features of international arbitration…is potentially significant to the claimant’s prospect of winning-and collecting the award.

Why Agree?

So before examining the consequences of becoming involved in international arbitration, it may be useful to reflect briefly on why parties agree to it in the first place. Are there clear benefits of international arbitration that outweigh the disadvantages of uncertainty inherent in the four factors mentioned?

The answer is: not necessarily. International arbitration is generally chosen by the parties not so much because they like it as because they have no other realistic choice.

There has been much discussion about the intrinsic merits of arbitration: speed, confidentiality, finality, special expertise of the arbitrator, inexpensiveness and whether these factors are real or illusory. Reasonable minds differ; they prefer either arbitration or court litigation. If like-minded negotiators are at work in a national setting, there will be no difficulty; arbitration will be chosen over court litigation, or vice versa. But if the negotiators are of different nationalities, the option most often evaporates because of the simple fact that the alternative court in the minds of the negotiators is not the same one.

Frenchman and Finn

A Frenchman and a Finn might-rightly or wrongly-both loathe arbitration, and neither would ever accept it when negotiating with fellow countrymen. When negotiating an international distributorship agreement, however, each finds it impossible to convince the other that the dispute should be heard by a judge in Paris or Helsinki, in the French or Finnish language, respectively. So they compromise, and their English-language contract is made subject to an arbitration clause calling for arbitration in London, Copenhagen, Zurich, or some other neutral place.

That is the reason that international arbitration-as opposed to domestic arbitration-is chosen. It prevails by default; there exists no neutral international court for private law disputes.

Unbridgeable Gap

A corollary of this observation is that international arbitration-along with more routine matters-gets the most intractable cases, where the parties’ positions are not only irreconcilable on the merits, but also separated by an unbridgeable gap of cultural and political misunderstanding.

As a result, the lore of international arbitration includes a number of stories of deserving parties who had to face absurd delays and complications, and spend an unconscionable amount of money, only to find that their award could not be enforced. These unfortunate cases should not be allowed to obscure the fact that international arbitration is the typical means by which international contractual disputes are settled, and that in most cases the process operates smoothly.

The growing popularity of mediation and conciliation, which first took root in the United States but have gained increasing support in other jurisdictions, reflects a high degree of frustration with the cost and delays often associated with traditional dispute resolution procedures.

Mediation and conciliation both involve a consensual (rather than adjudicative) process, often with the involvement of a neutral third party. Such forms of dispute resolution may loosely be described as “third party-assisted negotiation.”

Wide Use

Mediation and conciliation are now widely used in many countries, including the United States, the United Kingdom, Canada, Australia, Hong Kong, South Africa, New Zealand,

Germany, Holland and Switzerland.

The option of using mediation and conciliation procedures may be considered either at the contract drafting stage, by inserting a suitable clause in the contract itself, or after a dispute has already arisen.

Cooling Off

One advantage of the former approach (for example, by providing for a mandatory “cooling off’ period before either party commences arbitration or other proceedings) is that invoking the agreed procedure need not appear to be a sign of weakness.

However, mediation and conciliation should not be seen as “alternatives” in the sense of being substitutes for the adjudicatory process. The contract must contain an effective mechanism for referring the dispute to arbitration or to litigation in the courts, in case the consensual approach proves unsuccessful.

Recognize Weakness

Most forms of mediation and conciliation share the same essential features. The process is intended to encourage representatives of the parties to recognize the weaknesses of their own case and the strengths of their opponent’s case, as well as the wider commercial implications of the dispute.

By negotiating face-to-face, concessions can be made and opportunities for compromise explored without prejudicing the parties’ legal rights, at least until some form of binding agreement is reached.

Skills of Mediation

But it is the role of the third party- someone who is independent of the parties and able to view the dispute objectively- which is usually the crucial element. The success of any individual mediation or conciliation will largely depend upon the skills demonstrated by the mediator or conciliator in bringing the parties together and finding areas of agreement.

This is excerpted from ADR for Financial Institutions by Robert M. Smith (West Group, 2nd ed.1998,

1200 pp.) [Footnotes omitted]

Getting to the Table

Getting to the Table